Introduction

Every construction problem has a quality issue as one of its root causes. Poor contract conditions, failure to implement robust test regimes and inspection planning or to identify and remediate non-conformities to requirements,

and lack of adequate staff training lead to program delay, escalating costs and, if steps are not taken to deal with these quality issues, legal disputes.

As a Chartered Quality Professional with a degree in Civil and Structural Engineering and over 25 years’ experience working within the UK Major Infrastructure Project construction sector, I consider the introduction of the Building Safety Bill into law to be one of the most significant changes to the construction sector to have occurred during my career in the industry. In my opinion, the robust implementation of existing construction quality management tools and techniques, already used within the major infrastructure project sector are essential to the successful implementation of the requirements of the new legislation.

Unlike legislation for health, safety and environment standards, quality assurance requirements and the processes required to achieve and demonstrate them, have not been captured in law, save where provided for under individual contract arrangements. On the many major infrastructure projects I have managed, the client’s detailed requirements and expectations for quality assurance and certification have been incorporated into the project specific contract arrangements. I do not believe this to be standard practice throughout all sectors of the building industry. It is my hope and expectation that the forthcoming Building Safety Bill will introduce a requirement for construction quality and accompanying standards which are enforceable in law and which clearly attribute liability in the event of any breach.

The importance of the implementation of construction assurance in relation to the issue of building safety was clearly demonstrated during Dame Judith Hackett’s excellent webinar on the subject of “Quality in Construction” which I attended on the 23rd July 2020.

During the webinar, Dame Judith presented the background to and findings of her final report, Building a Safer Future – Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety (May 2018). With the aim of preventing a similar tragedy occurring in future, the report identifies lessons to be learnt and sets out a new regulatory regime to be implemented in response to the Grenfell disaster. The recommendations of Dame Judith’s report form the basis for the forthcoming Building Safety Bill, announced in this year’s Queen’s Speech on 11th May 2021.

Of the many insights Dame Judith shared during the webinar, one struck a particular chord with me, specifically the need to:

“Focus on delivering quality buildings which are safe and feel safe to live in.”

This phrase perfectly summed up Dame Judith’s key message, which is that there can be no excuses for the construction of unsafe, poor quality buildings. This expectation has long been true on major infrastructure projects.

Dame Judith also raised the following as key issues to be addressed :-

- Poor design change management and record keeping, both during construction, occupation and refurbishment.

- Unreliable and outdated product testing, marketing, labelling and approval processes.

- The need to provide clients with assurance and proof of quality of materials and processes used for any project.

- The need for subsequent building owners, occupiers and financiers to have proof of quality and competence.

As I stated earlier, I believe these issues can be addressed by the implementation of existing construction quality management processes.

In the Major Infrastructure Project sector, dating back to the Channel Tunnel Rail Link in the early 2000s, we have successfully operated robust processes for design management, materials testing and approval, competence assessment, progressive assurance and product certification. These processes are easily transferrable to the construction sector as a whole.

For example, setting aside the rail related systems (track, platforms, signalling, etc.), the remainder of a station structure is directly comparable with a complex residential building in terms of materials

used, trades employed (building services, cladding installers, etc.) and mechanical and electrical systems installed. Additionally, particularly for underground stations, issues relating to fire safety, safe evacuation in case of fire or other emergency are equally as complex and significant as those related to high rise buildings.

My intention for this article is to highlight the existing quality practices, tools and techniques that I believe are key to helping organisations meet the requirements of the Building Safety Bill. These practices are essential for the management of the construction, delivery and handover into service of safety critical projects, whether an underground station or a tall building used for commercial or residential or mixed use purposes.

The subjects I will cover in this article are appetite for risk, contract quality conditions, progressive assurance, self-certification, planning for compliance, compliance measurement and the new construction oriented quality standard.

Appetite for Risk

A concept that needs to be considered is that of client “Appetite for Risk”. What I mean by this is simply how much of the project risk is the client willing to retain themselves as opposed to delegating them to the main contractor/supply chain. Clients on major infrastructure projects normally demonstrate a low appetite for risk and retain a high level of control over project risks either by direct management and by implementing a robust level of intervention to ensure risk, where delegated, is properly managed. These clients are therefore prepared to invest in the resources required for the appropriate management of project risk even when the responsibility for risk management has been delegated to their main contractors and supply chain organisations.

I believe that clients outside the infrastructure sector do not currently employ a similar low appetite for risk model. One of the major implications of the Building Safety Bill for these clients will be the need to drive down their appetite for risk towards the levels I have experienced whilst managing major infrastructure projects.

Contract Quality Conditions (CQCs)

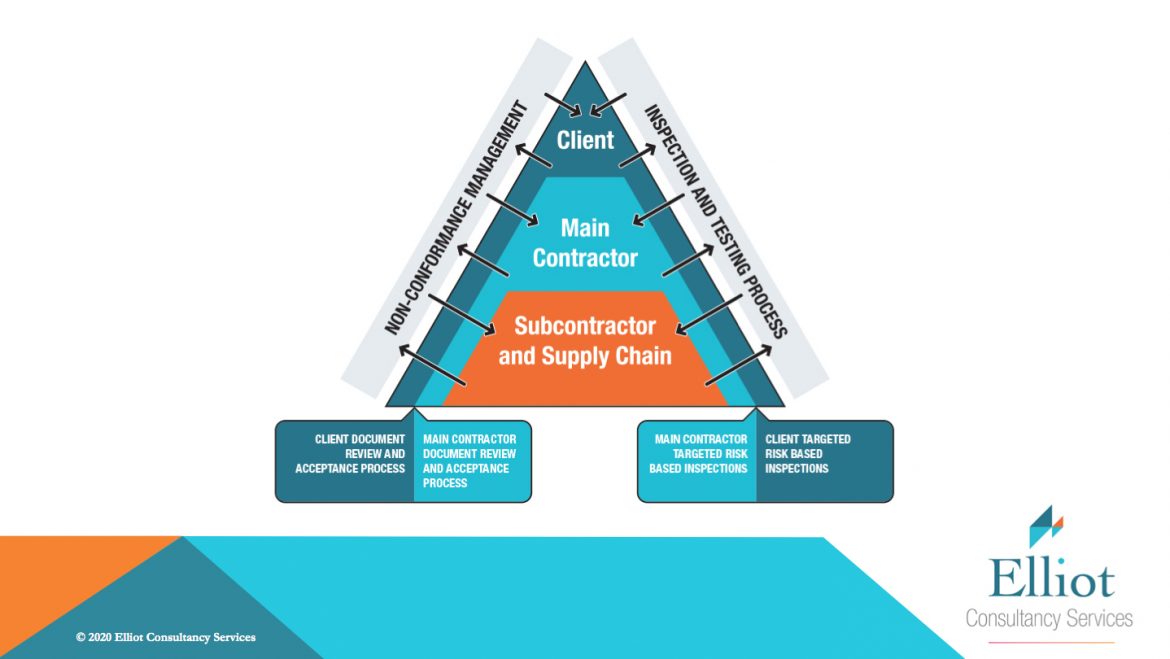

Clients with a low attitude to risk may also impose a robust set of quality requirements onto their main contractors, via contract conditions, which are generally then passed down through the project supply chain

I my experience, ensuring that an appropriate set of CQCs are in place at the start of a project is essential to the overall success of that project with regard to compliance and certification. CQCs allow the client to define their appetite for risk, set out clear and unambiguous rules of engagement, identify the project’s assurance methodology and quality culture and identify the required deliverables for compliance and handover. Most importantly they clearly define the responsibilities for quality delivery for all project participants.

Last year, I worked with the Chartered Quality Institute Construction Special Interest Group, of which I am a founder and Steering Committee member, to lead a working group which produced the

“Recommended Quality Requirements for Major Infrastructure Projects” document. This document outlines a best practice set of CQCs appropriate for high risk complex projects where the client has a low appetite for risk. This document is available on the Chartered Quality Institute Construction Special Interest Group website at 20200825_CQI-ConSIG_Quality-Requirements-for-Major-Infrastructure-Projects_Rev-1.0.pdf. While based on requirements for major infrastructure projects, the document can be modified to be suitable for various project sizes and types.

Ensuring that an appropriate set of contract conditions are in place prior to contract award will be a major factor in a client’s journey towards meeting the requirements of the Building Safety Bill.

Progressive Assurance.

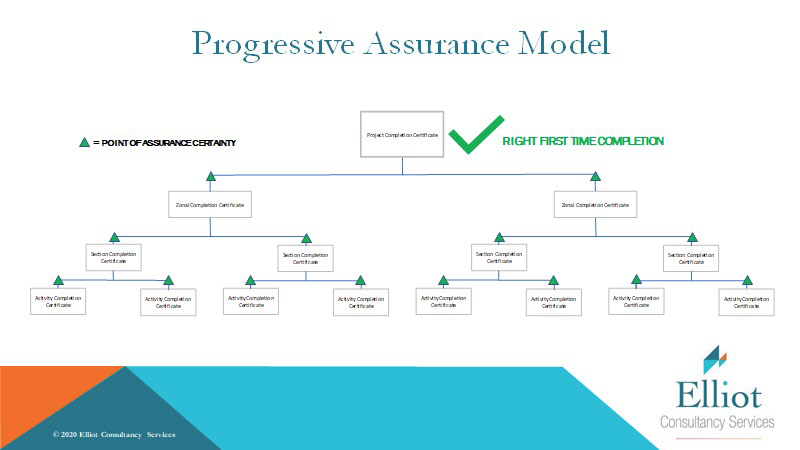

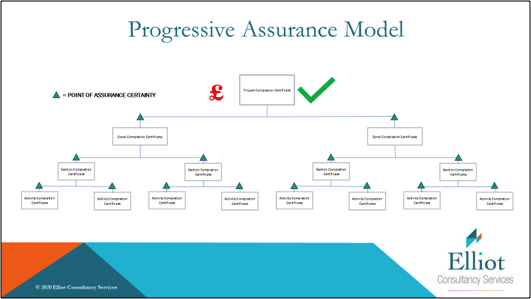

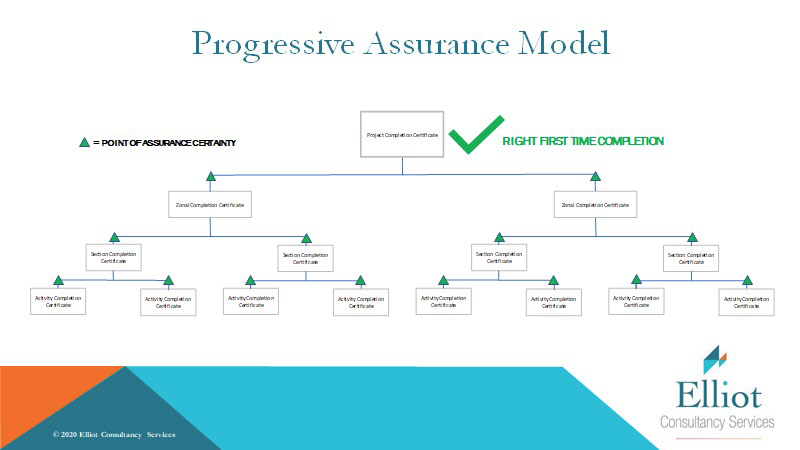

The progressive assurance model can be employed at all stages of a project from Gateway 1 (Planning), through to Gateway 3 (Completion) and will help create and maintain the “Golden Thread” of building information (hard copy or digital) envisaged by Dame Judith.

Progressive assurance supports the management of the planning, design, construction assurance and certification processes on a continuous basis at activity/trade level (design package, concrete frame, steelwork, cladding, etc.) and provides documentary evidence of compliance continuously throughout the project lifecycle. In essence, each activity/trade on a project is assured and certified as a mini-project, with each certification point forming ‘Points of Assurance Certainty’ (i.e. demonstrating that everything in the activity/trade is fully compliant, complete and assured to that point in the project as a whole).

Demonstration of compliance to the Building Safety Regulator is key to meeting the requirements of the Building Safety Bill. Building the compliance record continuously as a project proceeds in a systematic and robust manner is vital. The delivery of construction projects involves numerous subcontractors and suppliers many of which will have short durations on site, using the progressive assurance approach will ensure that the required compliance documentation is obtained from these organisations before they leave the project.

Self-certification

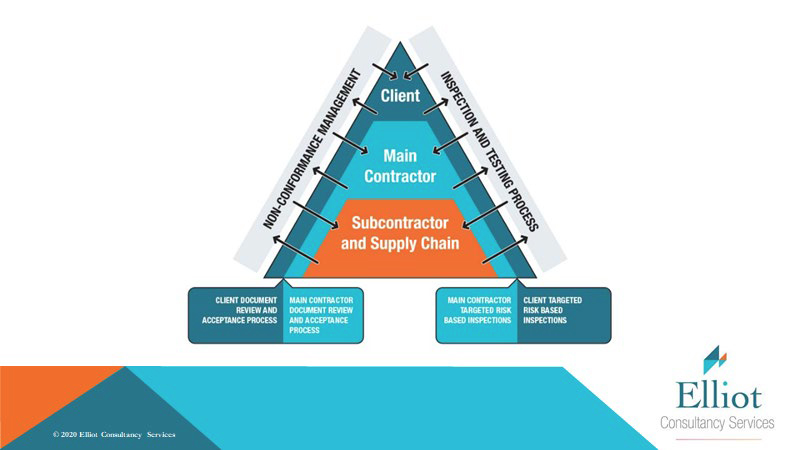

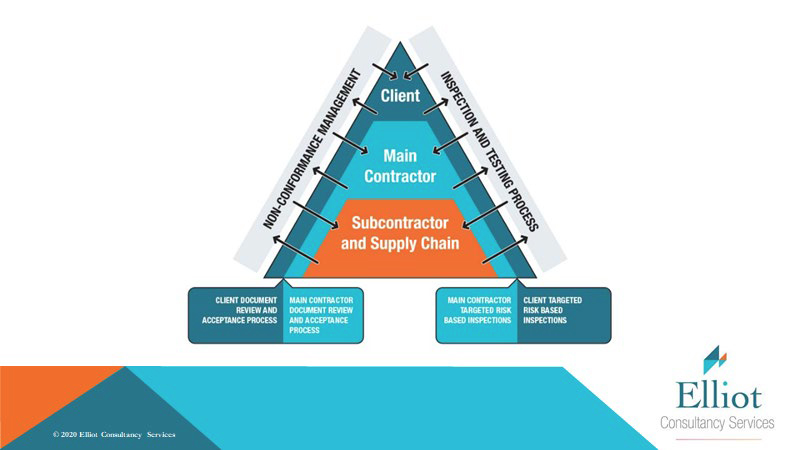

In my view, another key lesson that can be taken from the complex Major Infrastructure Project sector is the need to clearly identify and manage relationships between different stakeholders on any one project. In particular to ensure that each project participant fully understands their responsibilities with regard to compliance, the correction of non-compliant work and meeting the requirements of the Building Safety Bill.

Very few projects, whether large scale rail projects or high-occupancy residential developments, can be delivered in isolation by one company or organisation. Successful project delivery depends on the collaborative interaction between all project participants, including the client, the main contractor and the supply chain.

The use of the Self-certification model requires the definition and implementation of a robust and transparent assurance regime throughout a project. This ensures that all project participants are identified with their responsibilities and competency requirements clearly defined. It also promotes the clear collaborative framework and behaviours required to support a robust assurance process and will support project delivery right first time and promote compliance with the requirements of the Building Safety Bill. The model requires that clients and main contractors undertake risk based oversight of their supply chain partners using document review and inspection to avoid non-compliance at source and prevent the delivery and installation of incorrect or sub-standard materials. The use of the Self-certification model is key to the implementation of a low appetite to risk management system.

Planning for Compliance

The compliance of any product, activity or project cannot be left to chance, it must be actively planned throughout all stages of the project lifecycle. The responsibilities for compliance must be clearly defined for all project participants including the client, main contractor and supply chain partners as described above.

The most common tool used for planning for compliance is the Inspection and Test Plan (ITP) process (sometimes known as Activity Control Plans, etc.). They are required to support both the Progressive Assurance and Self-certification process.

In my opinion they are the cornerstone of the construction assurance process. When ITPs are subject to a holistic review and approval process including all project participants they provide part a key part of the process that demonstrates that project requirements have been correctly identified and understood by all parties.

ITPs are the key documents used to identify each of the activities, tests, inspections and record documentation required to verify compliance of a construction activity to the specified requirements. These record documents will form a major part of the “Golden Thread” of building information of information (hard copy or digital) envisaged by Dame Judith.

When used robustly the ITP should cover all stages of an activity including pre-construction (design, required competencies, etc.), materials approval/certification, the construction sequence (physical inspection and test) and completion (non-conformance, records and certification). The comprehensive use of the ITP process I have described here will actually go a long way to address the points I noted during Dame Judith’s webinar I mentioned earlier.

ITPs are often misconceived as a document that remains on the shelf in the office. It is essential that all relevant personnel, especially those undertaking the works, must be fully briefed on the requirements of the ITP prior to the commencement of the associated work. Evidence of these briefings must be retained.

Compliance Measurement

An often used and relevant quality related quotation is “you can’t manage what you can’t measure”.

The availability of contemporaneous and robust data is the tool which enables clients to determine where they are on the journey to compliance with the Building Safety Bill. It is also key to identifying issues at the earliest possible opportunity and enabling them to be corrected in real time.

In my experience one of the best quality tools to facilitate such measurement is the Quality Performance Index model (QPI). I have successfully designed and implemented the QPI process on recent major projects including Crossrail and Tideway.

The QPI model provides a simple one page graphic that quantifies the quality performance of an organisation or project based on performance against a bespoke set of quality KPIs, ideally using already available data.

The QPI Model supports the analysis, understanding and measurement of both internal and external requirements and can be used at all stages of the project life cycle.

When utilised across an organisation or project, it allows comparison of the quality culture/performance of the individual departments/sub-projects and can be used to benchmark quality performance and encourage continual improvement.

The new construction specific Quality Standard

The current international standard for quality management is BS EN ISO 9001:2015 – Quality Management System Requirements.

During my career this standard has moved from being targeted at manufacturing and engineering processes to become more generalist and therefore suited to all processes and organisations. One of the issues for the construction industry is that the standard has lost many of the detailed process controls required for the effective and efficient management of construction projects.

This problem has been acknowledged by the construction industry who have worked with the BSI to develop a more construction specific version of the quality standard. As a recognised expert in the field of construction quality management, I was invited to become a member of this committee alongside a broad spectrum of other stakeholders and have been involved in steering the new standard, BS 99001:2021 Quality Management Systems – Specific Requirements of the Built Environment Sector to the point of public consultation with publication due for late 2021.

Following the guidance of this new standard on construction projects will support compliance with Building Safety Bill.

Conclusion

The implementation of robust quality management tools and techniques such as appetite for risk, contract quality conditions, progressive assurance, self-certification, planning for compliance and compliance measurement are key to the success of all construction projects no matter the contract terms employed, their complexity or monetary value.

I believe that the implementation of the construction quality tools and techniques I have described in this article, if applied robustly by experience quality professionals, will help clients meet their responsibilities under the Building Safety Bill.